Alexander von Humboldt also lived and worked in Bayreuth in his day.

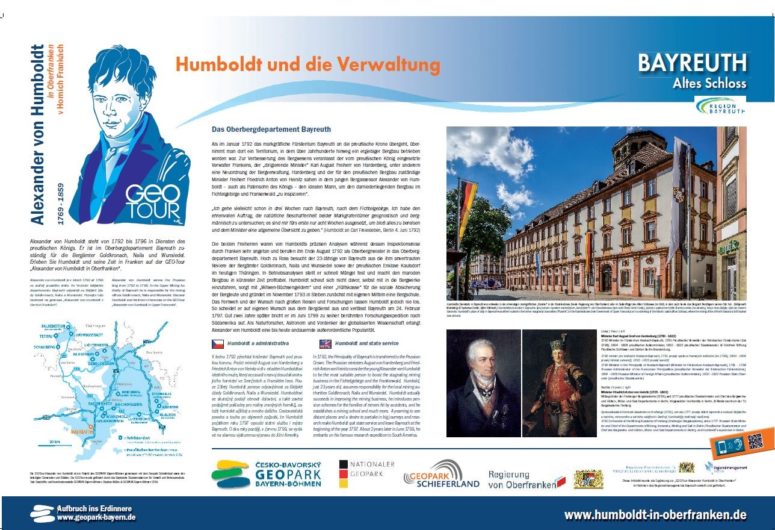

Alexander von Humboldt and Bayreuth 1792 to 1797 (by Stephan Müller)

I may be going to Bayreuth, to the Fichtelgebirge, in just three weeks. I have the honourable task of investigating the natural features of both margraviate territories from a geognostic and mining point of view; for the time being, I have only eight weeks to travel around and give the minister a general overview. What will happen after that, whether I will stay there completely (and become a mining director!!) or go to Silesia, is completely uncertain at the moment.

Alexander von Humboldt writing to Karl Freiesleben, Berlin 4th June, 1792 (In “Jugendbriefe”, p. 190) [1]

Alexander von Humboldt’s sense of excitement was very evident in his letter dated 4 June 1792 to his childhood friend Johann Karl Freiesleben. He had only just completed his studies at the Freiberg Mining Academy and already a high-ranking and responsible post awaited him in Bayreuth.

For only a few weeks before, Margrave Karl Alexander had ceded his two principalities of Ansbach and Bayreuth to Prussia in return for a life annuity of 300,000 florins a year. Karl August Freiherr von Hardenberg was appointed as governor of the new Prussian province. In order to establish Prussian law and order as quickly as possible, he brought top Prussian officials and outstanding graduates in all fields to Bayreuth.

Hardenberg and the minister responsible for Prussian mining, Friedrich Anton Freiherr von Heinitz, saw the young Alexander von Humboldt, who had just been appointed assessor cum voto in the Prussian mining department, as the ideal man to inspect the ailing mining industry in the Fichtelgebirge.

Humboldt’s first inventory

Alexander von Humboldt’s first assignment was a survey of the mines and smelters in the new Prussian provinces. On 26 August 1792, Humboldt presented a comprehensive report from his inspection tour to the Barons von Heinitz and von Hardenberg — first orally, later in writing.

They were impressed by Humboldt’s precise explanations, analyses and concepts for improvement and immediately put him in charge of mining and metallurgy in Bayreuth.

Full of pride, Humboldt reported to his friend Johann Karl Freiesleben in a letter dated 27 August 1792:

Yesterday I was appointed Royal Head of Mining in both of the Franconian principalities. All my wishes, good Freiesleben, have now been fulfilled. From now on my life will be devoted entirely to practical mining and mineralogy.

Humboldt writing to Karl Freiesleben, Bayreuth, 27th August 1792

(In “Jugendbriefe”, p. 209) – highlighted by Humboldt [2]

Taking up duty in Bayreuth

On 30 May 1793, he began his service as Head of Miner in the Prussian Upper Mining Department in Bayreuth.

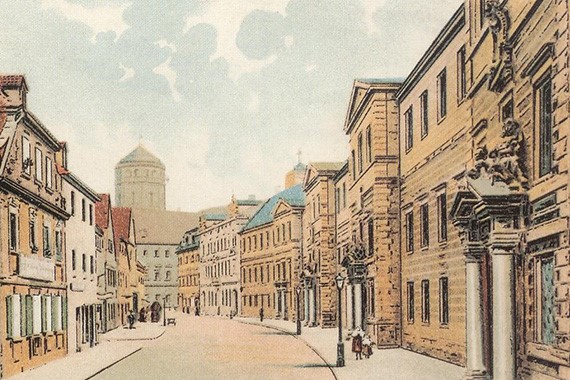

Even the Bayreuth city archives can no longer determine in which building the Upper Mining Department was housed. It is conceivable that Humboldt’s offices were in the former margravial state chambers, whose four large office buildings belong to today’s government of Upper Franconia. It is also possible, however, that they were in the Old Palace, where the Mining Authority of Northern Bavaria is located today.

Humboldt writes to Freiesleben from Bayreuth:

I have earned so much accolade with my mine reports that I have been given sole directorship of mining in the three mining districts of Naila, Wunsiedel and Goldkronach.[3]

On horseback, he visited and inspected the mining districts and their technical facilities, and devoted all his energy to the mining offices entrusted to him. One after the other, in February and March, Alexander von Humboldt carried out the general inspections of Goldkronach, of the Prussian enclave of Kaulsdorf, of Naila and of Wunsiedel, which took him around a week. In the operational analyses, he quickly identified the deficiencies and provided suggestions for improvement. The measures were implemented successfully. Within a very short period of time, Humboldt succeeded in making the ailing mines profitable.

Humboldt was not only praised by his superiors, but he also enjoyed great popularity among the miners, whose respect he had gained. He tried to improve people’s standard of living and security with funds for widows and orphans of miners who had suffered accidents, and ensured that surpluses from the mining offices were paid into a miners’ welfare fund to provide financial support for miners in need and to provide further training for ordinary miners.

The first school of mining

In November 1793, he founded a free royal mining school in Steben from his own funds in order to educate young miners and train skilled miners.

For 30 guilders, a bushel of grain and free wood and light, Georg Heinrich Spörl from Naila was employed as a teacher,[4] a young and clever shift foreman who not only had very good specialist knowledge but also understood the dialect of the Fichtelgebirge.

You could say that this established the first vocational school in Germany 225 years ago, where students between the ages of eleven and 16, but also some considerably older miners, eagerly took part in the lessons. In no other mining district at that time were young men from the mining industry given such a solid and practical education as in Steben.

To this purpose, Alexander von Humboldt provided textbooks and reference works that he had written himself, and even designed handouts, sketches and models for the lessons. [5]

The curriculum included:

- Arithmetic for miners

- Geology and mountain science

- History of mining law

- Basic knowledge about underground water

- Weather and local history

- Deposits

- Handwriting and spelling

Schooling ended with a public examination and awards for the best pupils, who found employment as miners in the Fichtelgebirge and Frankenwald areas.

Alexander von Humboldt’s wanderlust prevailed

From the middle of 1794 onwards, Humboldt’s desire for extensive travel and research became more and more apparent in his letters. He tells Friedrich Schiller in a letter dated 6 August 1794:

Perhaps I will soon be able to break away completely and devote myself entirely to the great scientific work I have set myself and which I am pursuing with great effort.

On 26 March 1795, Alexander von Humboldt asked to be relieved of his duties as head of mining. Karl August von Hardenberg and Friedrich Anton von Heinitz were able to prevent this resignation with a promotion to senior head of mining and more freedom for scientific travel.

However, Alexander von Humboldt wasn’t able to shake off his wanderlust. I am now seriously preparing myself for a long journey outside Europe[6], he wrote to Abraham Gottlob Werner at the end of 1796.

Secretly, he had probably known for some time that the position in Bayreuth could not be the fulfilment of all his wishes. It is a pity for Bayreuth that his wanderlust got the upper hand in the end, but also fortunate, otherwise his great later insights would have remained lost to the world!

Thus, at the end of December 1796, Humboldt left the mining service at his own request. He left Bayreuth on 24 February 1797.

Karl August Freiherr von Hardenberg showered him with unqualified praise. In his memorandum on the administration of the principalities of Bayreuth-Ansbach, he wrote that Humboldt’s services to the Bayreuth mining industry were tremendous [7].

GEO-Tour on Alexander von Humboldt as a mining official in Franconia now complete

To mark the 150th anniversary of Alexander von Humboldt’s death, the GEO Tour was devised and implemented in 2019. A total of 18 information panels explain the work of the young Prussian mining official Alexander von Humboldt at his former places of work in the Fichtelgebirge, in the Franconian Forest and now also in Bayreuth.

Nowadays, in Bayreuth’s city centre, in the courtyard of the Old Palace, at the busy passageway to the “Ehrenhof”, near the Mining Authority, which is now located in the rear building of the Government of Upper Franconia, there is a plaque to the “Upper Mining Department of Bayreuth”. The office was a port of call for Humboldt, who, as a mining official, was commissioned by the Prussian king to inspect the moribund mining industry in Franconia from 1792 to 1796.

Another information board awaits visitors at the entrance to the Ecological-Botanical Garden of the University of Bayreuth. It is well known that Humboldt, after his prompt resignation from the civil service, set off for the hitherto little-known world, to South America, to explore nature there. His approach of collecting and identifying plants and animals as well as surveying and analysing the geography and atmosphere is the basis of modern sciences such as ecology and geoecology. While working as a mining official in Franconia, he established the foundations for his systematic approach based on the recording of collected data.

Notes

• [1] Ich habe so große Pläne dort geschmiedet – Alexander von Humboldt in Franken, Frank Holl und Eberhard Schulz-Lüpertz, page 34

• [2] Ich habe so große Pläne dort geschmiedet – Alexander von Humboldt in Franken, Frank Holl und Eberhard Schulz-Lüpertz, page 49

• [3] Alexander von Humboldt und das Bergwesen, Erich Burisch, 1959, Archiv für Geschichte von Oberfranken 39, pages 245–291

• [4], [5], [7] ALEXANDER HUMBOLDT IN FRANKEN, Rudolf Endres, Mitteilungen der Fränkischen Gesellschaft Vol. 46, 1999

• [6] Lecture “Ungeheure Tiefe des Denkens, unerreichbarer Scharfblick und die seltenste Schnelligkeit der Kombination” (Immense depth of thought, unattainable perceptiveness and the rarest speed of combination) on Alexander von Humboldt by the science historian Herbert Pieper, Alexander-von-Humboldt-Forschungsstelle of the Berlin-Brandenburgischen Akademie, on 14th Oktober 2000 in Bad Steben. Source: Uni Potsdam